It is a strange thing to come back to the place you used to call “home” and start entering conversations that were already happening way back when you left, but that have evolved (or not) in your absence.

One such conversation I had with a friend sitting on a balcony last week when we were chewing the fat about how Germany is becoming more and more multicultural in a way that goes beyond the sort of immigration us Gen Xers experienced in the 70s and 80s. This is indisputably true following the influx of millions of refugees in 2015 and 2016. I cannot remember seeing that many non-white faces in public places when I lived here as a student. Which is encouraging. And yet, nothing much seems to have changed in terms of attitude of the “natives” of what is necessary to integrate old and new groups of German residents.

One attitude that still seems to prevail is about language. Talking to my friend she emphatically insisted that a condition of integration is that newcomers must learn to speak German. At least some of this attitude is borne from everyday frustration – she works in the medical arena and is at the sharp end of any barriers to communication when it comes to her patients. However, there seems to be some deeper issue there that speaks of power – specifically who has the power to determine which language is spoken in any given context.

Having lived in the UK for so long, this is a conversation that is not entirely unfamiliar. The British, too, have this expectation that everyone must speak English. Indeed, to this very day many British people do not just have this expectation in their own country but also in any other country they happen to visit. The joke that a “Brit abroad's” way of trying to be understood is to speak louder is as old as time and very much a reflection of reality, I fear. However, one thing that Britain did right for at least some of the time (much of this has changed in the last few years) is to acknowledge that there are in fact people speaking different languages living in the UK and that their needs should be catered for. In practice, this has meant that information published by public authorities or the NHS was often published in several languages including those of immigrant communities.

Nevertheless, most of that was an accommodation more than an actual acknowledgment of the fact that a country like the UK these days has more than one national language. And perish the thought that anyone should suggest such an official acknowledgement in today's super-sovereign, Rule Britannia, post-Brexit Britain. UK Twitter would probably collapse.

Similarly, my German friend, who is a good lefty liberal in almost all other ways, did not feel that her expectation was unreasonable. Of course, if you move to a different country, you should aim to learn the local language. And there is something seductive about that argument. Because it is an expectation that at least some of us also have of ourselves. If I, say, moved to Italy for retirement, the first thing I would do is, of course, a language course. But are all people, who insist that foreigners should speak the local language in their country, willing to return the favour when they themselves are the foreigners? The number of solely-English speaking retirees at the Spanish Costas suggests not.

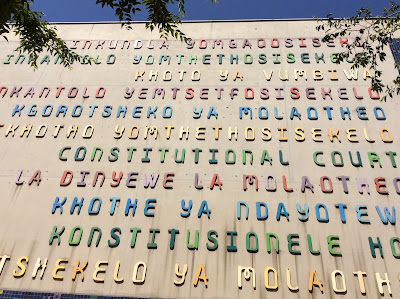

However, there is also a question even for those of us willing and able about where we put our efforts. Forget Italy! Which language would I aim to learn, if I moved, for example, to South Africa for retirement? The South African Constitution recognises 11 official languages: Sepedi (also known as Sesotho sa Leboa), Sesotho, Setswana, siSwati, Tshivenda, Xitsonga, Afrikaans, English, isiNdebele, isiXhosa and isiZulu. I already speak English, so would I actually bother to learn any of the others? And if so, which one would I choose?

The constitutional protection of these 11 languages is a direct reaction to the Apartheid regime, under which all of South Africa’s official languages were European – Dutch, English, Afrikaans. This was so, of course, because the Dutch and the British were the two main colonising groups that took control of parts of South Africa in 1652 and 1820 respectively before spending several decades fighting each other as well as the native population. So, if we all agree that those who move to another country should learn the local language, why did this not apply to those that colonised Southern Africa? Why was it indeed the native population that was expected to adapt instead?

The answer surely is because language is an expression of power, in this case of white colonialist power in action, given how very few white South Africans, even today, speak any of the native languages. Which raises interesting questions about the current fear of Europe’s white population with regard to the languages recent immigrant arrivals brought with them. Is it “colonisation” we fear? How Jungian of us to project that kind of shadow…

It gets even more interesting, if I chose to retire in Namibia, which has a similarly checkered history of European "arrivals". While several Portuguese explorers stopped by the country’s West Coast in the 15th and 16thcentury, it was again the Dutch who took control of Walvis Bay in 1793. They were quickly ousted by British settlers in 1805, but neither of them took over much of the country, which is arid and largely consists of desert. It was left to the missionaries to advance real settlements, most prominently those from Britain as well as my own German ancestors who arrived in the country around 1840. The Germans became particularly interested in Namibia during the “Scramble for Africa” in the late 19th Century when seven Western European countries colonised most of Africa. Bismarck established “German South West Africa” as a colony in 1884 on land previously purchased by German merchant Alfred Lüderitz from the Nama chief Josef Frederiks II (which is an interesting observation of the power of language in itself, given that a local Nama chief was probably not born with a name like that. So the fact that it is that name that has survived and made it into a 2021 Wikipedia entry tells us something.

Although the German tenure of power in Namibia was short – neighbouring South Africa launched a military campaign and occupied the German colony in 1915 – the German settlers remained in several parts of Western Namibia, particularly in Lüderitz, Swakopmund and Walvis Bay. Which is where they still are today, more than 100 years later. And guess what language they all speak? That’s right: German! You walk into any shop in Swakopmund as a white person and the shop assistant will immediately speak to you in accent-free German. There are German-only clubs ("Vereine"), German dentists, German guesthouses and German schools specifically for the local German population. Nearly two hundred years after their ancestors first arrived in the country the greatgreatgreatgreatgreatgreatgrandchildren of those original German settlers - African children all of them in outlook and identity - will speak German as their native language. And what's wrong with that?

Particularly since most of them will also speak at least one second language. But which second language? Again, judging by my own (anecdotal) experience, there is a dominance of other European languages including, in particular, English and Afrikaans. As far as I could tell, not many “SouthWesterners”, as they are still known, speak one of the native Namibian languages well enough to hold a conversation: Oshiwambo, Khoekhoe, Hereo, Kwangali or any of the many Bantu or Khoisan languages that are spoken by a smaller percentage of the population.

Indeed, even Namibia’s “national language” is English, despite the fact that less than 1% of the population speak it as their native language. This, too, was a political decision taken after independence from South African rule was finally achieved in 1990. It is now the language of government and administration.

Interestingly, though, while South Westerners, maybe understandably, insist on protecting their own heritage through the protection of the German language, the black population is often truly polyglot. The same is true for South Africa. Whenever I travel in that region and speak to people, I try to find out just how many languages everyone speaks. And it never ceases to amaze me that black South Africans or Namibians rarely speak less than four “tribal” languages on top of their own and at least one, often two, colonialist languages. So if I retired down there, which language, if any, would I learn?

And if I refused to learn any, what would that say about me? Would it be fair for people to claim that I was reluctant to integrate? Would a local doctor treating me for an injury in the Caprivi Strip be justified in her frustration about being unable to communicate with me? Would it be ok if people looked at me funny if I speak German on a bus in Durban because “Why can’t people, who come to live here, just learn Zulu?” Of course not, and we all know why. Because language is power and which language you are allowed or expected to speak in any context determines precisely where on the global food chain you are located.

So now I am in Germany. And because I still work in English and therefore still think in English, every now and then it happens that I address a shop assistant in a supermarket in English. Often I don’t even notice that it happens. And I do get funny looks sometimes. But mostly, people just assume that I am a tourist and either politely explain that they don’t speak English or, more often, they actually answer me in English.

On the basis of my conversation with my friend, I imagine that their reaction would likely be different, if I inadvertently defaulted to Turkish, or to Russian, or to Polish or to Zulu. Which tells you all you need to know. So whose responsibility is it to make sure that we can communicate with each other? And what does our answer to this question say about power, about us?